My use of Story Maps Journal responds to my disciplinary training in socio-cultural anthropology, from which one learns that the lack of information about the world’s cultures is endemic among undergraduate students, but also to larger concerns about reading carefully and about writing in the more general liberal arts tradition. I designed my first use of this digital tool for my freshman seminar in the Fall of 2016, which focused on the role of travel as a human experience. I used Story Maps in two different projects in the class, each focusing on a different text and designed for a different purpose.

As I learned to use the program (and this took some time), I discovered a rich tool for a number of my anthropology courses, and expect to use it in several. Story Maps’s design facilitates the relating of geographical/cultural knowledge, textual analysis, writing and research. I find that space and place are often abstract concepts for students who are involved in the process of studying cultural diversity; this program forces them to examine place in a new way.

This program also serves as a canvas for examining narrative and text, doing research, and placing it in the context of a “cultural product” (a concept developed by Emily Clark, a graduate of AC and a professor of comparative religion at Gonzaga) rather than simply a “project.” The product is public, providing an audience beyond the confines of the classroom. This quality, its use of different types of digital resources, its authorship, make it very appealing to students. I found them to be enthusiastic about the writing and research using this resource. In this course I was able to use the program to work on two particular sets of academic skills students need: textual analysis/reading skills, and writing skills.

Project One: Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia

The link to this map and the project is http://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=1fd9472d64524ecfbfe799a9e3dbf35b

The first project focused on Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, a travel account of Chatwin’s journeys through the Argentine and Chilean Patagonia during the mid-1970s. Chatwin begins his travels by acknowledging that Patagonia is the land at the end of the earth, perhaps the safest place to be were there to be a nuclear holocaust. His interest in the place stems partly from its distance, its isolation, and the unfamiliarity of its landscape to the rest of the world, so part of our project was to give the students in the class some familiarity with this unknown terrain.

But Chatwin’s book is also a kind of anti-travelogue; he makes few references to the actual landscape he travels through, often on foot or begging rides from passersby. Instead, the habitats he passes through are infused with stories, and it is these stories that he tries to capture. It is, in fact, a particular form of literature focused on storytelling and characters that come out of the landscape. The aim of the project, then was twofold. First, to allow students to become familiar with the landscape Chatwin describes, by tracing his route and doing some research on the towns, sites, and settings he encounters, and to see how those places might have influenced his writing and his stories. Second, to encourage students to read the text with greater scrutiny, carefully paying attention to the writing itself.

Travel writing is particularly fraught with the treacheries of translation. Written in part to lead readers into unknown terrains and unique experiences, the author of travel texts must also find a way to allow readers to find the familiar in the unfamiliar, to locate themselves in relation to the writer’s experiences. A travelogue that provides no context, that doesn’t connect with the experiences of the readers, risks losing their attention. Chatwin is accomplished in this delicate dance, knowing that most of his readers have never visited the Patagonia, and yet captivating them with stories that they can connect to. Thus, Chatwin dances between references to historical figures and current conditions (like Eva Peron, the guerrilla warfare Argentina was experiencing at the time of the writing, the historical figure Juan Manuel de Rosas, etc.), all part of the landscape he was traveling through and about which his readers might or might not have been familiar, and the stories of people in this isolated strange place that have some universal core to the human experience. It is his language, ultimately, that connects the reader with the place.

Our aim, for this project, is to write as a class a travel guide to the geographical Patagonia that Chatwin wandered through and to the Patagonia in Chatwin’s narrative. We will do this using the Story Maps program by ArcGIS.

Here’s how we will do it: each group/partnership will select some of the places Chatwin visited and use Story Maps to delve into Chatwin’s descriptions and stories. Your entries should give our readers some sense of the place Chatwin visited, and then, gleaning materials from Chatwin’s descriptions and stories, provide a sense of the significance the author gave to that place. As you create your entries you might think of some of the following questions:

- What have you learned about the place Chatwin has visited (I want you to explore this a bit), what are some of the impressions you have about this place (whether or not it conforms to Chatwin’s descriptions), and what characteristics of that place does he highlight or describe and fold into his narrative? What motivates him to select this place? By the way, how did he get there, and from where?

- Who are the characters he meets along the way? How does he describe them, and how are they connected to the place? In what ways are they “wanderers” themselves?

- What knowledge does Chatwin bring with him to give him insight into the locations or places he visits (he often visits a place to fill in stories that he already knew about)? On the other hand, what does learn when he visits the place and encounters the characters of the place?

- Many of Chatwin’s stories are about past events. What connections does Chatwin make between the past and the present in his descriptions?

- What techniques does Chatwin use both to engage you in his travels to that place and to engage you in his story?

Your entries should be one or two page thoughtfully written essays that may incorporate other materials like photos, links to videos and maps. Remember, the aim is to provide the reader of our guide a sense of what Chatwin is up to. You will be evaluated on the how well you capture both the characteristics of the place and more importantly, how well you capture a sense of what Chatwin is attempting to convey.

Project 2: Che Guevara’s Motorcycle Diaries

The link to this project is http://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=b54a55069c374bbc852714a911b96b31.

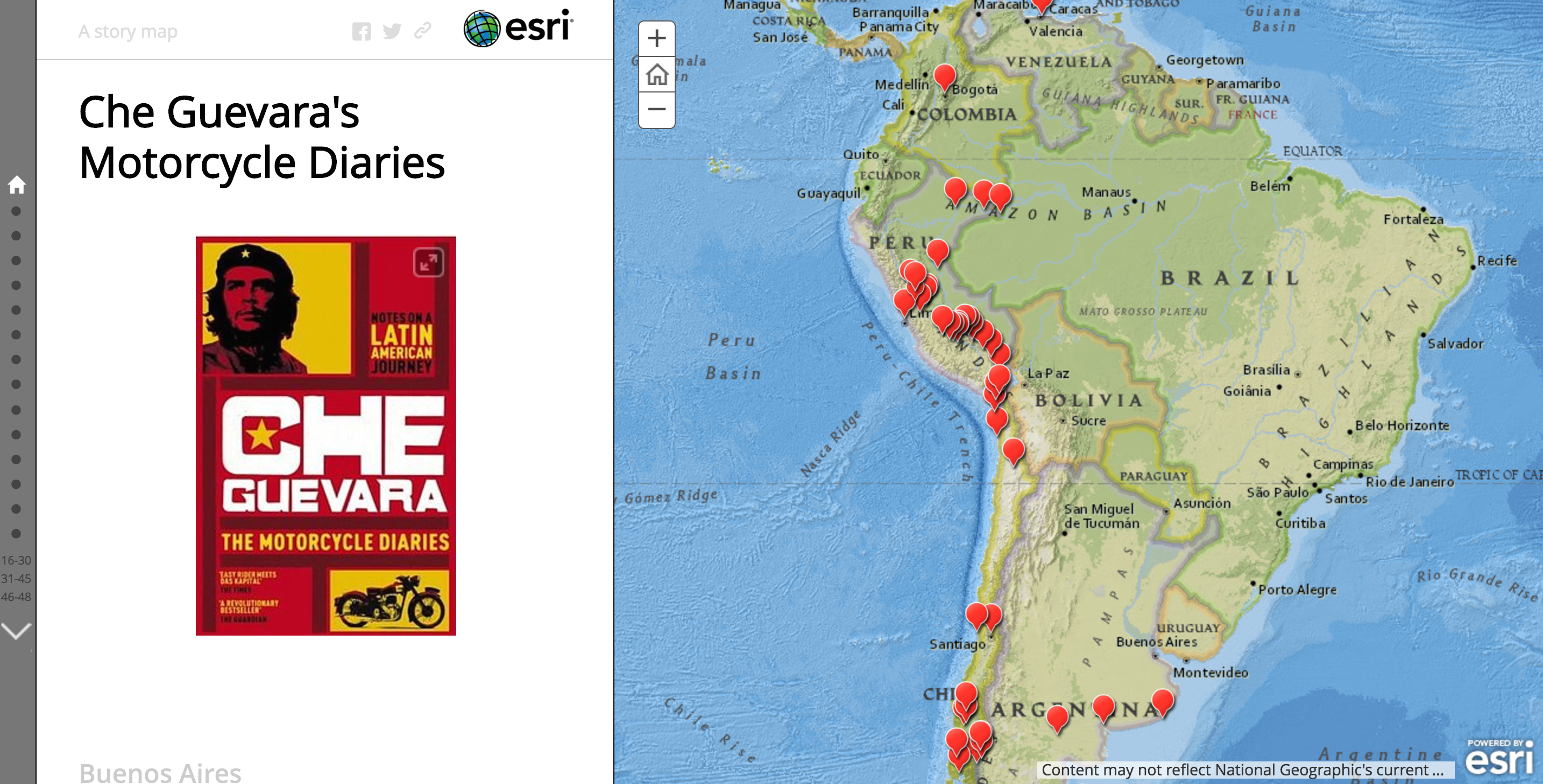

The second Story Maps project focused on Ernesto Che Guevara’s Motorcycle Diaries, a travel diary written during the young Che Guevara’s travel up the spine of Latin America as a medical student. This project examined the entries in the text critically, asking students to see what in the natural and social landscape had helped radicalize the diarist. A map was drawn of all the locations Che and his companion Alberto Granados had experienced during their 6 month journey. Students were to select one of those sites and examine Che’s entry against the past and current reality of the site.

Travel is often described by its practitioners as a transformative experience. Long-term travelers point to the gradual letting go of long held expectations and habits, learning new perspectives, developing new values; travel experiences often combine the processes of “letting go” and allowing new orientations to take root. Some travel with this purpose in mind (it’s a favorite theme of travel writers); in other cases the “conversion” comes unintentionally and without warning. Certainly this was the case of Che Guevara, who as a young medical student, embarked on continental motorcycle trip. Who could have foreseen that this traveler, a member of Cordoba’s landed gentry, a kind of serious young careerist, would become a world renowned revolutionary fighter and theoretician?

In later life, Che recognized this journey as a transformative experience, the beginning of his investiture in revolutionary causes; as he edits his diaries he states: “The person who reorganizes and polishes [these notes], me, is no longer, at least I’m not the person I once was.” Patrick Symmes (Chasing Che: A Motorcycle Journey in Search of the Guevara Legend), who retraced Che’s trip, noted in his book: “Every long journey overturns the established order of one’s own life, and all revolutionaries must begin by transforming themselves.”

In this project we are going to look at landscapes that Che traveled through and examine what about his experiences in those places might have contributed to his transformation. Each member of the class will select a leg of the trip and write an “interpretive essay” examining two things that about that part of the trip:

- First, drawing on the diaries themselves, think about how Che might have experienced and seen what he saw on that leg of the trip. In other words, drawing on his own reflections, think about how he might have experienced that stage of the journey. You might think as well about how Che reacts in his diary to these experiences, and what that might tell you about “who he was” at that moment.

- Second, what about this leg of Che’s trip might have stirred his rising consciousness about social conditions in Latin America. What do you see in this landscape that might have nudged him in that direction?

Your interpretive essay should be no more than a page in length, and placed on our Story Map program. I’d like you to be creative and convincing in writing your Story Map entries. Each entry will be evaluated on the quality of its writing, on the quality of explorations both into Che’s account and into the landscapes he passes through, and on its creativity.